They say, “Any publicity is good publicity,” but PR professionals looking at Kyte Baby’s recent press would likely disagree. The small Texas-based online baby apparel startup came under fire for denying an employee’s request to work remotely as she was caring for her newly adopted preemie infant. The employee took to TikTok, garnering viral support for her cause, and leading to two apologies from company representatives, one scripted and an off-script follow-up.

While this story brought instant and widespread outrage, situations like this are nothing new for many Americans, and no doubt many will read this story with disbelief – not at the company’s treatment of the employee – but at the fact that this situation is surprising to the public. Like it or not, from the available facts, it seems that Kyte Baby has met its legal obligations and the minimum standards that both the federal government and the state of Texas impose. For many companies, an employee’s entitlement begins and ends with the mandated legal requirements.

What was Kyte Baby obligated to provide?

Federal Family and Medical Leave Act: Though this employee was requesting remote work, could she have been entitled to take a leave of absence to care for her new child?

The federal Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) requires that employers with 50 or more employees provide 12 weeks of leave to employees who have worked for the employer for 12 months and have logged 1,250 hours within the 12-month period prior to the leave request. On top of that, the employee must work at a worksite with 50 or more employees within a 75-mile radius. From internet sleuthing, it appears that Kyte Baby is based in Texas and maintains about 13 employees. With that information, unless they’ve grown significantly, they are not a “Covered employer” under the FMLA. According to media reports, the employee in question had been employed by Kyte Baby for seven months. Even if Kyte Baby was a larger employer, this employee would not have been eligible for FMLA benefits due to her insufficient length of service.

State Leave of Absence: Turning to state leave mandates, we come up short in Texas. In 2019, Dallas enacted the Earned Paid Sick Leave Ordinance that would have required employers in the city with 6 or more employees to provide at least 80 hours of leave that could have been used, among other reasons, to tend to a child needing medical attention. The State of Texas sued the city, and in 2021, a federal district court judge deemed the law in violation of the state constitution. Kyte Baby, located just outside of the city, likely would not have been subject to the law due to its location, but as it stands, no employer in Texas is required to provide their employees with anything beyond the federal mandates. Texas is not alone in this: most states do not provide significant job protection beyond the basic FMLA requirements. If you follow the news in the absence field, it can seem that there are major developments daily to improve leave rights for employees. But it’s a large country, and most states still do not provide any significant rights – paid or unpaid – beyond the FMLA.

Could Kyte Baby have been more generous with parental leave?

Yes, but carefully. According to media coverage, the company’s policy at the time offered only a two-week paid parental leave, and of course, it should have provided access to that benefit (which it may have done). But when it comes to FMLA coverage, as a general matter, an employer cannot loosen up the coverage or eligibility requirements to provide FMLA rights to employees when they are not eligible. A simple hypothetical will illustrate:

Scenario: Marco was hired in October 2023 by BespokeCloke, a handcrafted cloak outfitter located in Wyoming with 51 employees. In March of 2024, Marco’s father falls ill, and Marco needs to take six weeks of leave to care for his father while he recovers. BespokeCloke decides to be generous and even though Marco hasn’t been employed for 12 months prior to the start of his leave, they grant him his FMLA rights early. Months pass, and Marco and his spouse adopt a child. In November of 2024, after reaching his 12 months and 1250-hour threshold, he requests 12 weeks of FMLA leave to bond with his new child. BespokeCloke informs him that since they granted him FMLA leave in March, he only has six weeks left this year to bond with his new child. Marco objects, explaining that in March he was not an FMLA-eligible employee, so the time he took then could not have counted against his FMLA allotment.

Who is right?: The U.S. Department of Labor has held that an employer must follow the requirements of the FMLA in designating time as FMLA leave: no more and no less. The DOL has addressed two specific examples of this principle: an employer cannot delay designation of the FMLA to allow an employee to stack other sick leave with FMLA, and an employer may not provide additional FMLA leave beyond the 12-week FMLA entitlement. While the DOL has not specifically opined on whether an employer can grant FMLA eligibility prematurely, employers would be wise to exercise caution here. While designating Marco’s absence as FMLA leave prior to meeting eligibility requirements may sound more generous, the employer cannot do so to the detriment of his future FMLA entitlement.

How can an employer manage this? This technical reading of the FMLA may be cold comfort to an employee who has no leave rights in March of 2024 prior to reaching FMLA eligibility. If the employer cannot prematurely grant FMLA rights, what can they do to help? An employer can offer its own company leave policy to provide leave rights to employees before they become eligible for FMLA. For example, they can offer an employee who has not met the FMLA’s eligibility requirements up to 12 weeks of leave for the same reasons, available for use in their first 12 months of employment. That time cannot count against their FMLA allotment.

Why would an employer provide extra benefits? Many employers recognize the employee as a whole person with needs outside of the workplace and proactively want to provide generous benefits. Thus far, we are talking about unpaid leave – the right to take time off and be reinstated upon return, not the right to be paid during this time. As such, while there is undeniable financial impact, it is limited. Moreover, whether leave is granted under the FMLA or a company policy, employers can require documentation for the time off to ensure it is being used according to the law or policy’s requirements, i.e. legitimate medical needs or to bond with a new baby, for example. And while this can still present a challenge to employers, the expense of staff turnover cannot be understated: a multitude of studies on this topic indicate the costs of turnover can range from a few thousand dollars to over 200% of an employee’s salary. Altruism aside, a leave of absence may be the least expensive option for the employer.

Could the Americans with Disabilities Act help?

Even if the FMLA doesn’t apply, doesn’t the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) provide some coverage for an employee, especially if she is asking for an accommodation to work from home, as in the case of Kyte Baby’s employee?

The ADA applies to employers with 15 or more employees, so for the sake of argument, let’s assume Kyte Baby meets the threshold of a covered employer. And the ADA has zero eligibility requirements, so there is no need to meet an hours or months of service requirement. Surely her hospital-bound baby qualifies this employee for accommodations under the ADA or state law?

Here, the answer is almost definitely no, at least in Texas.

Under the ADA, a disability is defined as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.” However, key to this analysis is that, unlike the FMLA, it is the employee who must be suffering from a disability to be entitled to ADA protection. The disability of a family member does not qualify an employee to an accommodation under the ADA. In this case, Kyte Baby’s employee cannot rely upon the ADA for an accommodation.

One caveat to this is the concept of an associational disability: an employee cannot be discriminated against based on their association with a family member with a disability. For example, an employee who has a disabled child cannot be turned away from employment due to a perception that they will be an unreliable employee. But under the ADA, an employer is not obligated to provide that same employee with a reasonable accommodation, even if their family member clearly has a disability. Employers in two jurisdictions – the state of California and the city of Pittsburgh — should exercise caution, however when it comes to associational disabilities and accommodations. California has enacted the California Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA), a state counterpart to the ADA that provides broader protections. Relying on FEHA, two courts in California have opined that the duty not to discriminate against an employee due to an association with a family member with a disability extends to the obligation to provide a reasonable accommodation. Beyond that, Pittsburgh has enacted a law mandating reasonable accommodations for the needs of both pregnant workers and their partners.

This is not to say that the employer should not voluntarily offer an accommodation to an employee in the form of remote work, a leave of absence, or some other arrangement that is mutually beneficial to the employee. But based on the facts available, Kyte Baby does not appear to have run afoul of either the FMLA, ADA, or other state law

Many Americans face gaps in absence entitlements

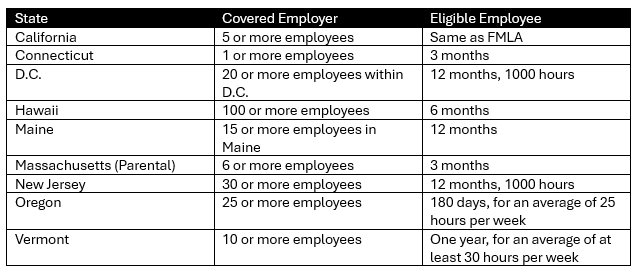

There remain significant gaps in the patchwork of absence entitlements in the U.S. that leave many Americans vulnerable in their most difficult moments. U.S. Small Business Administration statistics indicate that almost half of U.S. employees work for small businesses, over 90% of which have fewer than 20 employees, rendering these employees unprotected by the FMLA (like the employees at Kyte Baby). A handful of states have passed more generous versions of unpaid FMLA-type laws. Note that these laws provide leave for reasons that overlap but, in most cases, do not align exactly with the FMLA. A sample of these expanded entitlements are shown below:

While states continue to expand upon their unpaid entitlements, like the recently enacted California reproductive loss leave and Illinois expanded bereavement entitlements, the biggest area of progress is in state Paid Family Medical Leave (PFML) expansions. State PFML programs not only target employee income replacement, but also many are making significant inroads when it comes to job protection. In Part II of this story, we’ll discuss how PFML programs at the state and federal level are working to fill gaps in our leave landscape.

That’s likely small comfort to Kyte Baby, faced now with a reputation crisis and loss of brand value from the TikTok turmoil. Kyte Baby has no shortage of critics with something to say; if those critics redirected their energies toward understanding the holes in our leave and absence safety nets and finding constructive ways to address them on a comprehensive scale, parents and employers alike would benefit on a broader basis, not just at a single micro-employer in Texas.

Read FINEOS Kyte Baby blog part II for more on paid sick leave and PFML.

FINEOS compliance experts like Lori help ensure customers with FINEOS Absence and FINEOS IDAM stay up-to-date with the latest changes to federal, state and local leave laws. To find out more about our leave solutions, contact us.