Turns out that life insurance industry’s relationship with information technology didn’t begin with computers.

Before World War I, the opportunity arose to leverage so-called tabulating machines, originally developed by Hermann Hollerith for the United States census of 1890.

Predecessors to computers, these large wooden machines used punched cards for fast counting, sorting, adding and later, printing.

Hollerith’s company went on to become IBM, so this was clearly a foundational era for both sides.

Some things have changed since then. Cubicles, for one. Hairstyles, for another. Hemlines.

Some things have changed since then. Cubicles, for one. Hairstyles, for another. Hemlines.

What has certainly changed is the industry’s early-century reputation as a pioneer of information technology. There was a natural fit, as insurance was all about collecting, processing and communicating information. And there wasn’t much need for specialized hardware, as in banking. The industry gamely leaped in and earned respect from other industries for doing so.

Whatever became of that good start?

Overall, reading the history of this first dalliance with technology adoption, one is struck by the uncanny similarities to today. Are some attitudes and behaviors just in the industry’s DNA?

If so, are we doomed to repeat them?

1. Departmentalism

“Organisations often produce systems with structure that mirror their own structure” – Conway’s Law

Not unique to our industry by any means, but we have long been a case study of repeated action at departmental level. For example, the underwriting, premiums and claims departments evolved for their tabulators their own single-purpose variants of ‘Customer Card’.  But the goal of a multi-purpose enterprise ‘Master Customer Card’ remained elusive – foreshadowing today’s quest for that elusive 360o single customer view.

But the goal of a multi-purpose enterprise ‘Master Customer Card’ remained elusive – foreshadowing today’s quest for that elusive 360o single customer view.

2. Baby Steps

When presented with the tabulator opportunity, the industry chose continuity and slow change over real transformation. Speed up current work practices rather than reinvent them. Sound familiar?

When presented with the tabulator opportunity, the industry chose continuity and slow change over real transformation. Speed up current work practices rather than reinvent them. Sound familiar?

One theory attributes this to a sensitivity on the part of paternalistic insurers to their employees’ job-displacement fears. However, it’s more likely attributable to the perennial challenge of business re-engineering. Leaders recognized (not always quickly) that the full benefits of IT could only be accessed through process re-design.

Then, as a hundred years later, most found this too hard – an enduring barrier to modernization.

3. Think Different

“Our fundamental proposition is that the Metropolitan is big enough, and its work important enough, so that we do not have to fit our system to existing machines; that time is not imperative; that the Metropolitan, rather than propose a plan to fit existing machines, can demand that machines be built to fit its system” JD Craig – Actuary, Met Life (1914)

Life insurance has always seen itself as a place apart, too special and complex for outsiders to easily understand. Things were kept in house. Rather than bringing in professional technologists, insurers trained existing employees to configure and operate the new machines, slowing innovation.

The same patterns of exceptionalism were exhibited by individual firms.

As seen in the quote above, Met Life chose the customization route, drowning one tabulator vendor (Pierce) in years of unique requirements, but ultimately little value realization.

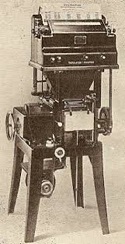

Prudential, the US version, ignored the product route altogether and built their own machines. Optimized for Prudential’s high volumes of industrial business, the so-called Gore Sorters, designed by Chief Actuary John K Gore, were a good fit initially…in 1895…but were soon outpaced in all performance categories by the market-powered Hollerith machines.

Prudential, the US version, ignored the product route altogether and built their own machines. Optimized for Prudential’s high volumes of industrial business, the so-called Gore Sorters, designed by Chief Actuary John K Gore, were a good fit initially…in 1895…but were soon outpaced in all performance categories by the market-powered Hollerith machines.

Perhaps the most enlightened approach was taken by the Prudential Life Assurance Company of London, which collaborated with the Powers Tabulator Company, influencing the product direction but from a respectful distance, while openly encouraging the vendor’s commercial success. They succeeded in cutting their expense ratio almost in half.

4. Frenemies

A hundred years ago, exactly as today, the industry had a schizophrenic ability to collaborate closely in some areas and omit or refuse to do so in others. Through professional bodies and conferences, actuaries, as a tribe, transcended company barriers, collaborating on data standards, regulations and on the possibilities of new technology.

On the other hand, there was, and remains little, sharing or convergence in operational matters. What common patterns do exist have arguably arisen simply from administrative people moving between carriers. This divergence is now an Achilles heel for incumbents as a group in the face of new market entrants.

5. Full Circle

While actuaries led technology adoption in the 1910s and 1920s, the operating divisions took firm control from mid-century. The reporting line of IT often simply moved from the CFO to the COO. Since then, risk and finance professionals have usually had to make do with whatever data emerged out of the backwash of systems built for operational needs.

However, after that long hiatus, things are coming full circle as modern core systems take a rounded multi-persona view, giving due weight to the needs of ARF systems (Accounting-Risk-Finance) designed for users, but built for the whole firm.

6. Largest First

The belief in early part of the 20th century was that only the largest insurers could bear the cost of exploiting new technologies. As the technologies matured, it was said, smaller companies could get in on the action. While the larger firms adopted technology one department at a time, smaller carriers were advised to implement the whole suite. This was at one point termed the “consolidated functions” approach. These patterns were laid down early and the beliefs have endured to modern times.

There is however a contrary view emerging that smaller carriers can today outmanoeuvre their more bureaucratic and encumbered big brothers. With technology becoming ever more adoptable, the chief obstacles are increasingly the extent of legacy baggage and organisational inertia, both of which weigh heaviest on the giants.

We will see …

7. Oh, it does this too?!

For many decades, and in fact until quite recently, it proved difficult to establish any direct correlation between companies’ spending on information technology and productivity gains (e.g. as measured by cost ratios).

This isn’t to say there weren’t gains, of course, but many of them were emergent in nature. For example, while many insurers implemented technology for labor savings, they later discovered and exploited benefits for customer service, operational insight, staff retention and accuracy.

Sometimes you just gotta’ move.

Conclusion

One puzzle throughout the decades: Why has adoption not been more urgent historically, especially given the evident benefits of technology?

Does regulation dampen true price competition?

Do investment returns drown out other drivers of financial results?

Has the long-term steady growth of the market focused competitive activity on sales and channel reach versus back office efficiency?

With the ‘new tech’ barbarians at the industry’s gates, the stakes are now higher.

Awareness of the past is a form of strategic advantage.

Awareness of the past is a form of strategic advantage.

It’s interesting to see fake news reviving interest in history.

History, in our context suggests that the winners in technology adoption today will be those who:

- Leverage products

- Adapt to those products

- Think holistically

- Challenge themselves to take leaps

Which players can transcend the pull of past behaviors to survive and thrive?